Historic Names and Places on the Lower Mississippi River

(Madison Parish, Louisiana Portion)

By Marion Bragg

Mississippi

River Commission 1977

MADISON

COORDINATOR’S NOTE – The

following has been excerpted (and slightly reformatted) from Historic

Names and Places on the Lower Mississippi River by Marion Bragg – an

out-of-print 1977 publication of the Mississippi River Commission. Although

this book begins just below Cairo, Illinois and ends at the Gulf of Mexico, only

the Madison Parish portion is included here. Distances quoted are miles above

the River’s Head of Passes (AHP), about 95 miles below New Orleans. RPS June

2006

Mile

461.0 AHP, Map 32

In the 1829 edition of The

Western Pilot Captain Samuel Cumings reported that Eagle Bend was assuming the

same shape that the old Horseshoe Bend had taken just before the river cut it

off. The river's currents were working on the neck of Eagle Bend on both sides,

and Cumings predicted an early cutoff.

More than 20 years later,

engineer Charles Ellet examined the bend and said the neck had grown extremely

narrow, and that some "misguided and ignorant persons" had dug a

ditch across it. Only diligent effort by planters in the area had prevented a

cutoff from occurring, Ellet thought.

Local people in the Terrapin

Neck area complained after the Civil War that in 1863 Admiral David D. Porter

had sent a party of soldiers and seamen to Eagle Bend with orders to try to

effect a cutoff. The falling river had frustrated the efforts of the Union

forces, but the ditch across the neck had been enlarged by the soldiers and was

causing the river to flood their fields whenever the water rose to flood

stages.

On March 7, 1866 the cutoff

that had been predicted for more than half a century finally occurred. Terrapin

Neck had narrowed until it was only about 30 feet wide, and the channel that

the river cut across it enlarged very rapidly. On March 28 it was reported that

the little steamer Lida Norvell had come down through the new cutoff

instead of taking the bendway, and her captain said he believed the new channel

was now safe for all boats.

Eagle Bend soon silted up at

both ends and became the oxbow lake that is called Eagle Lake. For many years,

Eagle Lake was widely known among sportsmen as one of the finest fishing lakes

in the South, but pollution has created many problems in recent years. The

swamps and forests that made the vicinity of Eagle Bend an ideal habitat for

the Bald Eagle were cleared away, and the use of agricultural chemicals on the

surrounding plantations contaminated the waters of the lake. A control

structure designed to prevent pollution is now under construction by the Army

Corps of Engineers. Sportsmen hope that when the structure is completed the

lake will recover most of its former productivity.

ISLAND NO. 102

Mile 459.5 AHP, Map

32 Left bank, descending

During the Civil War, a

refugee camp was established on Island No. 102.U. S. military authorities

placed the camp under the supervision of government agents and teachers, and

ordered them to teach the freedmen to be self-supporting.

The experimental project at

Island No.102 was already floundering in red tape when Confederate forces were

rumored to be in the vicinity. Many of the blacks fled the island, fearing that

they would be taken back into slavery. The ones who remained were soon pressed

into service on a confiscated plantation where a northern speculator was

struggling with the mysteries of how to get rich growing cotton. Families were

separated, there was much misery, and the government quietly washed its hands

of the whole affair and abandoned the project.

Mile 457.1 AHP, Map 32 Right bank, descending

A steamboat accident near

Omega Landing is the apparent basis of a number of imaginative stories that

persist to this day. The boat involved originally was a steamer called the Iron

Mountain. The accident was not a spectacular one. The steamer simply ran

upon a snag, started to sink, and was safely abandoned by everyone on board.

Early the next morning some

of the boat's officers went out to investigate the condition of the sunken

steamer by daylight. It was nowhere to be found. Assuming that it had been

swept down the river, they reported the loss to the owners and found themselves

positions on other steamers. A couple of months later, it was reported that the

Iron Mountain had been located. She had apparently been swept through a

break in a levee shortly after the accident and was reposing peacefully in a

cotton field where the falling water had dropped her near Omega Landing.

From this rather commonplace

incident, many fabrications have arisen involving great steamboats that passed

a river town loaded with passengers and then disappeared from the face of the

earth without a trace. Fiction, when presented “as a true story” can be much

more entertaining than fact!

Omega Landing today is the

site of a new port that is being developed by the inland town of Tallulah,

Louisiana, and the parish officials of Madison Parish. Port authorities have

acquired and prepared an industrial site on the landside of the levee, and two

industries are already established on the site. In 1974 the Corps of Engineers

constructed an industrial fill where local interests expect to expand an area

to attract more port industries.

Omega was an early cotton plantation established before the Civil War.

Mile 456.0 AHP, Map

32

Milliken’s Bend was named for

an early settler in the area, and was the site of a prosperous little community

before the Civil War. In 1858 it was said to contain several fine stores, a

school, and some impressive homes. The steamboat landing was a busy one, for

there were many rich and fertile cotton plantations in the area.

In January, 1863, Milliken’s

Bend was swarming with Union transports that had brought a Union army under

General William T. Sherman down the river to make an attack on the city of

Vicksburg. The fleet had arrived in the bend on Christmas Day, 1862, and many

of the steamers bore familiar names. The John J. Roe, City of Memphis, R.

Campbell Jr., Sunny South, Universe, Empress, Sam Gaty, Die Vernon, Fannie

Bullitt, Crescent City, Henry van Phut, and Nebraska were all river

steamers that had been converted from civilian to military use. When Sherman's

campaign ended in disaster, the steamers disappeared from Milliken’s Bend for a

time, only to reappear shortly thereafter with General Grant's army.

While General Grant was

trying to find a safer way to approach the city of Vicksburg, some of the Union

soldiers were encamped at Milliken’s Bend. Every day they were marched to

Duckport Landing (Mile 445.7 AHP), where they were digging a canal that was

supposed to provide access to the Tensas River, and thence to Red River. The

Duckport canal was completed, and trees and drift were being cleared from a

small bayou that would connect it with the Tensas when the Mississippi began a

rapid fall. The falling water made the canal perfectly useless, but it also

opened up a land route that Grant could use to march his army to a point below

Vicksburg. Gathering all his troops together at Milliken’s Bend, the Union

general started on his long road to Vicksburg by way of Grand Gulf and the

interior.

When the troops moved out,

Milliken’s Bend was made a depot for Union army supplies. A detachment of white

soldiers and two black regiments were posted as guards. On June 7, 1863, rebel

forces attacked the post. The Confederates had pushed the Union garrison out of

its fortifications and to the water's edge when the Union gunboats Choctaw and

Lexington appeared on the scene. The rebels fled.

Since the Union troops had

suffered heavy losses in the engagement, and since black regiments had been

involved, the northern press cried, "Massacre!" Admiral David D.

Porter, curious about the affair, went ashore, climbed the levee, and looked

into the fortified post, He reported that he saw about 80 black soldiers dead

inside the post, and an equal number of dead rebels lying dead on the parapet

outside. According to the evidence he could obtain, Porter thought the

engagement had been "a fair fight."

After the Civil War, the

river's currents attacked the site of the old town and it soon disappeared.

Mile 452.7 AHP, Map

32 Right bank, descending

In the flood of 1927, the

Lower Mississippi reached unprecedented high stages. At Cabin Teele plantation,

the water overtopped the levee and washed it away, creating a crevasse more

than 1,000 feet wide. Several thousand people who lived in the affected area

were stranded on ridges, rooftops and levees. Three days later, some were still

awaiting rescue. Small boats were sent up from Vicksburg with food and

provisions for the refugees, and larger ones followed to bring the people back

to Vicksburg.

Vicksburg had more than

10,000 flood victims encamped in a tent city during the flood of 1927. People

for miles around came to stare at the refugees. On Sundays, sightseers were so

thick that committees were appointed to direct the traffic.

Mile 450.0 AHP, Map 32

The bend of the Lower

Mississippi River that was removed by Marshall Cutoff had long been subject to rapid

erosion on the east bank. As it grew longer and longer, engineers feared that

the Mississippi was going to cut its way into the bed that the Yazoo River had

abandoned in 1799. The consequences of such a change would have been disastrous

for the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, where the waterfront had been restored

in 1903 by diverting the Yazoo into the Mississippi's old bed in front of the

city.

To avoid commitment to a

long and costly revetment program that might or might not have succeeded in

holding the river out of the old mouth of the Yazoo, the Army Corps of

Engineers constructed the artificial cutoff across Marshall Point in 1934. By

August, 1937, the Mississippi had accepted the cutoff as its new channel and

the danger of a change that would have given the Yazoo a new mouth was averted.

PAW PAW ISLAND

Mile 449.5 AHP, Map 32 Left bank,

descending

The small tree called the

Paw Paw is common in the Mississippi Valley. It has a maximum trunk diameter of

about ten inches, and its wood is of no economic value. The fruit of the Paw

Paw is three to six inches long, and is edible in October, or especially after

a frost. It is cylindrical in shape, pulpy in texture and is borne in cluster

of two to four. A single fruit can weigh more than half a pound.

Paw Paw Island lay close to

the right bank of the river and belonged to Louisiana. Marshall Cutoff moved it

to the Mississippi side, and it is now attached to the east bank of the river.

It is also designated as Island No. 103, and during the early history of the

river had the odd name of "My Wife's Island."

YOUNG’S POINT, LOUISIANA

Mile 442.8 AHP, Map 33 Right bank, descending

Young’s Point, on the Louisiana

side of the river just above Vicksburg, is today one of the most tranquil

places imaginable. Nothing disturbs the quiet of the rural countryside but the

occasional throb of a diesel towboat gliding past the point, or the chug of a

farmer's tractor in one of the nearby bean or cotton fields.

In 1863, Young’s Point was

literally covered with thousands upon thousands of Federal soldiers, and a

whole fleet of Union Navy vessels were tied up in the willows along the shore.

General U. S. Grant was in command of the Union army, and Admiral David D.

Porter commanded the Union fleet. Vicksburg, on the opposite bank of the river,

was their objective. It was the third attempt against the rebel stronghold. A

Union fleet under David Farragut had tried to take it in the summer of 1862,

and the effort was a dismal failure. A Union army under General William T.

Sherman had tried again at the end of 1862, and had suffered a humiliating

defeat. Grant and Porter were going to try it again. They arrived at Young’s Point

in January, 1863. and it would be six months later before they would see the

inside of the Confederate fortifications at Vicksburg.

Between Young’s Point and

Vicksburg, the Lower Mississippi made a long, long bend in 1863. Union vessels

that attempted to pass the fortified city on the bluffs were exposed to the

merciless bombardment of the rebel guns.

General Grant began his

Vicksburg campaign with a half-hearted attempt to build a canal across Young’s

Point. After the Civil War, the big ditch would be labeled "Grant's

Canal," but it would have been more correct to call it "Lincoln's

Canal." Someone had proposed the project to the President in 1862, and he

had ordered General Thomas Williams to begin its construction while Farragut

bombarded the hill city opposite the point. General Williams had lost most of

his men from disease and had withdrawn in disgust when Farragut's fleet went

down the river after failing to silence the guns at Vicksburg.

The U. S. Secretary of War

had told General Grant that President Lincoln was taking a personal interest in

the canal that was designed to cut Vicksburg off from the Mississippi. It was

made perfectly clear to the stolid General Grant that his own personal opinion

of the practicability of the idea was irrelevant. President Lincoln said

"Dig!" and the general shrugged his shoulders and put his men to

work. The project would at least keep his boys occupied while he explored other

possible means of getting at the confounded city on the bluff.

General Grant reported on March 6. 1863 that the Secretary of War could

inform the President that the Young’s Point canal was almost completed and

would soon be opened. The next day the rising Mississippi breached the dam at

the upper end of the canal, and the work had to be halted. It was never

resumed, but experiments were made at other sites. None succeeded, but General

Grant was undismayed. His "providential failures." he said later,

forced him to try the land routes that eventually led him to success and

national fame when he captured Vicksburg.

General Grant reported on March 6. 1863 that the Secretary of War could

inform the President that the Young’s Point canal was almost completed and

would soon be opened. The next day the rising Mississippi breached the dam at

the upper end of the canal, and the work had to be halted. It was never

resumed, but experiments were made at other sites. None succeeded, but General

Grant was undismayed. His "providential failures." he said later,

forced him to try the land routes that eventually led him to success and

national fame when he captured Vicksburg.

During the campaign that

followed the unsuccessful effort to bypass Vicksburg by digging the canal, a

camp for convalescent Union soldiers was established at Young’s Point. When a

small detachment of Confederates launched an attack on the position on June 6,

1863, a clever Union officer drew up the convalescents in battle lines that

deceived the rebels and caused them to flee without a fight, believing

themselves to be greatly outnumbered.

More than ten years after

the Civil War ended, the Mississippi made its own cutoff at Vicksburg, and left

the city of Vicksburg without a waterfront.

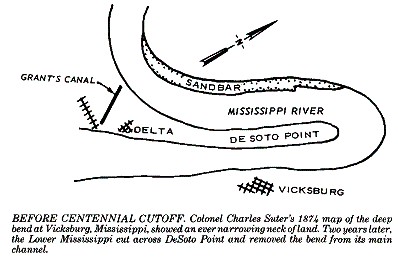

CENTENNIAL CUTOFF

Mile 437.5 AHP, Map

33

At 2:10 p.m., April 26.

1876, the Lower Mississippi took one last bite out of a narrow neck of land in front

of the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, and went surging across DeSoto Point,

Louisiana. The river had done what General U. S. Grant and more than 50,000

soldiers had failed to do in 1863. The old town of Vicksburg was removed from

the Mississippi.

The cutoff that occurred

while the nation was celebrating its 100th Anniversary came as no surprise to

residents of the area. For many years, eminent civil and military engineers had

been examining the narrow neck of land in front of the city and predicting that

the river would soon cut through it.

Before the cutoff occurred, many people had argued that a cutoff would

have little if any effect on Vicksburg. The old bend would remain navigable,

they said, and the town would therefore retain its waterfront. The city's docks

would continued to be as busy as ever. Others predicted gloomily that a cutoff

would cause the old bend to fill with silt, that the point opposite would

recede, and that Vicksburg would be left on a shallow oxbow lake, two miles

from any potential steamboat landing.

Before the cutoff occurred, many people had argued that a cutoff would

have little if any effect on Vicksburg. The old bend would remain navigable,

they said, and the town would therefore retain its waterfront. The city's docks

would continued to be as busy as ever. Others predicted gloomily that a cutoff

would cause the old bend to fill with silt, that the point opposite would

recede, and that Vicksburg would be left on a shallow oxbow lake, two miles

from any potential steamboat landing.

The pessimists were correct. Vicksburg had lost its

waterfront. At low water, a vast expanse of sand and mud prevented steamers

from entering the river's old bed, and the docks in front of the city were

silent and deserted for months at a time. Vicksburg would stagnate for a

quarter of a century before the Army Corps of Engineers would build a canal

that would restore the town to its former status as a river port.

The pessimists were correct. Vicksburg had lost its

waterfront. At low water, a vast expanse of sand and mud prevented steamers

from entering the river's old bed, and the docks in front of the city were

silent and deserted for months at a time. Vicksburg would stagnate for a

quarter of a century before the Army Corps of Engineers would build a canal

that would restore the town to its former status as a river port.

VICKSBURG,

MISSISSIPPI

Mile 437.1 AHP, Map 33 Left bank,

descending

The bluff where Vicksburg,

Mississippi, is located today was the center of a power struggle between

European nations for more than a century before the town itself was founded.

Jean Baptiste LeMoyne, Sieur

de Bienville, had tried to establish a military post and plantations in the

area in the early 1700's, but the French settlement was wiped out by hostile

Indians. Just before the American Revolution began, British subjects who were

loyal to the mother country and wanted no part of the coming struggle asked

permission to plant a large settlement on the lands that lay between the Yazoo

and Big Black Rivers. The Revolution disrupted the Tory plans, but enough

British land grants were made to cause plenty of grief to the American settlers

who would later move into the area.

Spain seized the Natchez District in 1781, and claimed that the mouth of

the Yazoo River was the northern boundary of Spanish West Florida. The new

American government disagreed, but preferred not to fight for the district that

had become known as "the Walnut Hills." While diplomats argued the

case politely, Don Manuel Gayoso de Lemos. Spanish commandant of the Natchez

District, heard that an American land company was preparing to bring several

thousand armed men down the river to establish an American colony on the bluff.

Gayoso set out at once with a detachment of Spanish soldiers and workmen, and

began the construction of a military post that he called Fort Nogales. Nogales

was the Spanish word for "walnuts."

Spain seized the Natchez District in 1781, and claimed that the mouth of

the Yazoo River was the northern boundary of Spanish West Florida. The new

American government disagreed, but preferred not to fight for the district that

had become known as "the Walnut Hills." While diplomats argued the

case politely, Don Manuel Gayoso de Lemos. Spanish commandant of the Natchez

District, heard that an American land company was preparing to bring several

thousand armed men down the river to establish an American colony on the bluff.

Gayoso set out at once with a detachment of Spanish soldiers and workmen, and

began the construction of a military post that he called Fort Nogales. Nogales

was the Spanish word for "walnuts."

Victor Collot, a French

general who made a voyage down the Mississippi in 1796, sneered at the

fortifications the Spanish had constructed on the bluff in 1791. The Spanish

had blundered from hill to hill, adding on little outposts, he said, and the

whole complex could be overwhelmed in a few minutes by any handful of

determined men.

The small detachment of

American regulars under Captain Isaac Guion who politely requested the

withdrawal of the Spanish soldiers from Fort Nogales in November, 1797, may

have had a similar opinion, but they were under orders not to provoke Spanish

authorities. When the Spanish commander of the fort firmly refused to give it

up, the Americans went on down the river to Natchez to wait patiently for the

Federal government to work out its dispute with Spain. In March, 1798, the

Spanish abandoned Fort Nogales.

An American garrison moved

into the old Spanish fortification and renamed it Fort McHenry. American

settlers in search of cheap land followed hot on their heels, and a small

community of farmers was soon established in the area. Among them was Newit

Vick, a Methodist minister from Virginia. Vick purchased a land claim from a

restless pioneer and began raising cotton on the bluff. It soon occurred to him

that the bluff he owned would make an ideal location for a town. He took a

piece of paper and a pencil and sat down and drew a plan. His city was to be

called "Vicksburgh "

Vick sold two lots before he

and his wife succumbed the same day to the ravages of fever, and died, leaving

thirteen children as their heirs. The executors of Vick's complicated Last Will

and Testament thought that his plan to establish a town was a good one. They

placed an advertisement in contemporary newspapers. It read as follows:

"VICKSBURGH: On the Second Monday in April next, will be offered at Public Sale, LOTS in the recently laid off Town of Vicksburgh. This Town is situated on the east bank of the Mississippi river, Warren county. Mississippi state, 90 miles above Natchez, 55 from Jackson, the Seat of Government, 14 below the mouth of the Yazoo river, 2 below the Walnut Hills, and is thought by many persons to possess advantages superior to any other site on the Mississippi river, above New Orleans. Its local situation is truly desirable, combining all the advantages of health, air and prospect—having an elevation fifteen feet above high water mark, gradual ascent back for near a half mile, and possesses a commodious landing. The country, the traffic of which must center at this place, is extensive and fertile (embracing a greater part of the late Choctaw purchase) and will admit of good progress. Purchasers will have a credit of one, two, three and four years, by giving bond and sufficient security, with interest from the date. The sale to be on the premises. John Lane, Adm'r with the will annexed of the late N. Vick, deceased. February 16. 1822.

The public auction was a

great success, and Vicksburg (it dropped the "h" in later years) was

on its way into the future. The advent of the steamboat, the invention of the

cotton gin, and the removal of the Indians had made it a sure thing.

Shopkeepers moved in to take advantage of the growing trade in cotton and

plantation supplies. Doctors moved in and offered their skills, and often their

lives, in the yellow fever, smallpox, and cholera epidemics. Lawyers moved in

to help untangle the conflicting claims of settlers under British land grants.

Spanish land grants, squatter claims, and purchase from the U. S. Government In

one of the many disputes a question arose as to exactly when Vicksburg became a

town. Was it founded by Vick when he drew his plan and sold the first lots in

1819 or did it come into existence as a town after the public sale? A high

court decreed that when Newit Vick drew up his plan in 1819, he had founded the

town. Various accounts of the town's history, however, have given dates ranging

from 1820 to 1825 as the date of its establishment.

The town of Vicksburg was

incorporated by the Mississippi legislature in 1825, and it became the county

seat of Warren County. By the time the Civil War opened in 1861, it was a busy,

flourishing river port with a population that was considerably larger at the

time than the nearby capital city of Jackson. Many of Vicksburg's citizens were

foreign-born, a large number came from states other than Mississippi, and few

who were living in the town in 1861 were born there. Practically allot them, in

spite of their diverse origins, were dedicated "southerners" but many

of them were stubbornly opposed to disunion.

Before the war began

officially, local militia in Vicksburg, with some help from the State, planted

a battery of guns on the waterfront and created a national furor by stopping

boats and searching them before allowing them to proceed down the river.

The Port of Vicksburg, with

its fine slack-water harbor that was constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers

and opened in 1960, has attracted small industries and river-related businesses

to the town. The port terminals handle more than two million tons of cargo

annually. Some of the products handled are grain, petroleum, lime, cement,

steel, and paper products from International Paper Company's mill north of the

city. The 245-acre industrial park constructed by local interests is already filled,

and plans are under way for expansion. Vicksburg is growing steadily, and

promises to become an important distribution center for the waterways

industries and waterborne commerce. Like other river towns, it is benefiting

from the development of improved boats and barges, navigation aids, and the

maintenance of a safe and dependable navigation channel on the Lower

Mississippi. The port handled 2,864,131 tons of cargo in 1974. Improved harbor

and terminal facilities, and new concepts of shipping will lead to further

development.

Mile 437.1 AHP, Map 33 Left bank,

descending

The diversion canal

constructed in 1903 by the Army Corps of Engineers diverted the Yazoo River

into the Mississippi's old bed in front of Vicksburg and restored the town's

waterfront. There is a marina for pleasure boats at the public landing in front

of Vicksburg, where water, electricity, showers, and laundry facilities are

available for pleasure boaters.

The Yazoo is a tributary of

the Lower Mississippi and formerly entered the big river several miles above

Vicksburg. With its tributaries, it drains approximately 13.355 square miles of

delta and hill land in the northwest quarter of the State of Mississippi.

In 1699, the Tunica Indians were

occupying villages along the banks of the Yazoo. Father Antoine Davion, a

French missionary priest, established a mission among the Tunicas in 1699, but

reported that he made little progress in converting them to Christianity. In

spite of their disinterest in his religion, the Tunicas were fond of the

priest, and when they fled the Yazoo to avoid a war with their enemies, they

took him with them to a point farther down the river.

The lands the Tunicas

deserted were soon taken by three small tribes—the Koroas, Ofagoulas. and

Yazoos—who banded together and became known as the Yazoo Nation. French

colonists established a military post and some plantations on the Yazoo around

1718, and coexisted with the Yazoos until 1729, when the Indians launched a surprise

attack on the post and killed Father John Souel, a French Jesuit priest, and

the handful of soldiers and settlers in the area. The French abandoned the

Yazoo river and made no further effort to establish settlements in its

vicinity.

Choctaw Indians claimed the Walnut Hills area when the Spanish built

Fort Nogales there, and the vast area of swamps and bottomlands that lay

between the Yazoo and the Mississippi above the Spanish fort remained

uninhabited by white settlers until after the Choctaws were removed in the

1830's.

Choctaw Indians claimed the Walnut Hills area when the Spanish built

Fort Nogales there, and the vast area of swamps and bottomlands that lay

between the Yazoo and the Mississippi above the Spanish fort remained

uninhabited by white settlers until after the Choctaws were removed in the

1830's.

During the Civil War, the

Confederate forces hid a large part of their fleet in the Yazoo after the fall

of Memphis and New Orleans. Most of the boats were sunk to prevent them from

falling into Union hands. After the Civil War, local steamboat interests

requested the Corps of Engineers to clear the stream of all the obstructions.

Eleven or twelve of the old wrecks were removed, and one of them was the hulk

of a merchant vessel called the Star of the West. This was the steamer

that President Lincoln had sent to Fort Sumter in 1861 with reinforcements, and

it had been on the receiving end of the first guns fired in Charleston Harbor.

Later the boat had been captured by rebels, and they had brought it to the

Yazoo when New Orleans fell into Union hands.

The Union gunboat Cairo,

the victim of an ingenious rebel torpedo in 1863, was not removed from the

Yazoo. The gunboat remained buried in the mud and silt until it was resurrected

one hundred years after it had gone down. Hundreds of relics were recovered

during the attempt to raise the Cairo in 1962, and many of them are now

on display in the visitor's center of the Vicksburg National Military Park. The

gunboat itself was considerably damaged when raised and was sent to the Gulf

Coast, where it still awaits funds for restoration.

The Yazoo River has always

been considered a navigable stream, and plans for its improvement have been

authorized. When funds become available to carry out the Federal project for

its improvement, it is expected that the river will be navigable for 97% of

each year. At present, a few towboats enter the Yazoo from time to time, and in

1974 almost a half a million tons of grain and agricultural chemicals were

transported by barge on the Yazoo.

For more than a century, the

lower part of the Yazoo Basin served as a storage reservoir for floodwaters

that backed into the tributary from the Mississippi at flood stages. In recent

years, there has been a great deal of land clearing and swamp draining in the

lower basin, and a flood-control project is now under construction by the Corps

of Engineers. It is designed to provide protection for the backwater areas at

high stages of the big river and would be overtopped only by a project flood.

KENT’S ISLAND-RACETRACK

TOWHEAD

Mile 431.5 AHP, Map 33 Right bank, descending

When the Corps of Engineers

dredged out a new channel on the east side of Kent’s Island, the old

Reid-Bedford Bend was removed from the main channel of the river. The bend had

been named for two Louisiana planters whose cotton plantations adjoined it.

Opposite Kent’s Island, there was once a small town called Warrenton.The

legislature of the Mississippi Territory had created the town in 1809, ordering

it established because the new county of Warren had to have a county seat. The

location chosen was low, flat, and surrounded by swamps. After Vicksburg was

established a few miles up the river, Warrenton was doomed. It could not

compete with the city that had a better landing, a higher location, and a

vigorous leadership that was determined to make the most of Vicksburg’s

advantageous location. The seat of county government was moved to Vicksburg,

and Warrenton went into a long, slow decline.

Opposite Kent’s Island, there was once a small town called Warrenton.The

legislature of the Mississippi Territory had created the town in 1809, ordering

it established because the new county of Warren had to have a county seat. The

location chosen was low, flat, and surrounded by swamps. After Vicksburg was

established a few miles up the river, Warrenton was doomed. It could not

compete with the city that had a better landing, a higher location, and a

vigorous leadership that was determined to make the most of Vicksburg’s

advantageous location. The seat of county government was moved to Vicksburg,

and Warrenton went into a long, slow decline.

During the Civil War,

Confederate forces constructed a fortification at Warrenton, and its guns

succeeded in putting one of the Union Navy's vessels out of action on April 22,

1863. The Union boat involved was called the Tigress, and she had safely

passed all the Vicksburg batteries before one of the rebel guns at Warrenton

scored a direct hit, causing her to go aground and break apart. The crew was

saved, but the boat was a total loss.

Badly damaged by shelling

during the war. Warrenton struggled on for a short time afterward until the

river moved west, leaving the village landlocked. It was then abandoned, and

all that remains today is an old cemetery on top of a nearby bluff.

Islands No. 104 and No. 105

were in the Reid-Bedford Bend, and disappeared from navigation maps when the

headway was cut off.

DIAMOND CUTOFF

Mile 425.5 AHP, Map 34

Diamond Cutoff was the first

artificial cutoff constructed by the Corps of Engineers in the 1930's. There

had already been several natural cutoffs in the area, and engineers believed

that the river was about to create another at Diamond Island. To forestall the

natural cutoff, the engineers began the construction of the artificial channel

which was designed to keep the river channel in a more desirable alignment than

the river itself might have chosen.

Work commenced in the fall

of 1932, and the new channel was opened on January 8, 1933. It developed slowly

but satisfactorily and eventually became the permanent bed of the Lower

Mississippi.

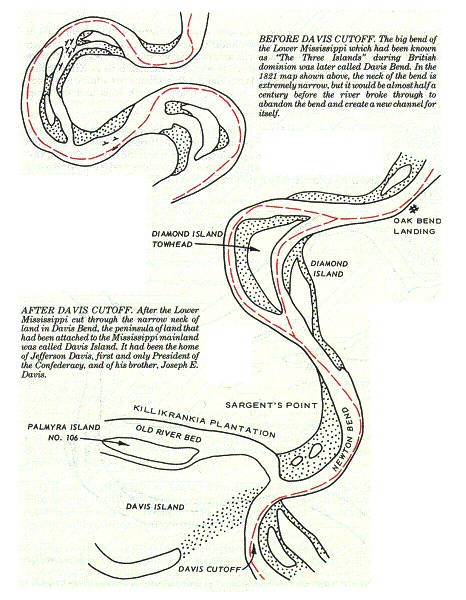

Mile 415.5 AHP, Map 34 Right bank, descending

The course of the Lower

Mississippi in the Davis Island area has changed many times during the past two

centuries.

In 1776, when American

revolutionaries were putting the finishing touches on the document they called

"A Declaration of independence," loyal British subjects were asking

the British King for grants of land on a great bend of the Lower Mississippi

that was located a short distance above the mouth of Big Black River. In the

bend were three small islands, and the British settlers called the area “The

Three Islands."

One of the British subjects

who succeeded in obtaining a small grant of land at The Three Islands was

William Selkrig, a hard-working, peace-loving Tory who built himself a small

cabin on the river bank, cleared away some of the ancient trees, and began to

cultivate his soil in 1777.

In January 1778, Selkrig saw

a strange armed vessel approaching the landing near his cabin. The armed vessel

was called the Rattletrap, and was under the command of an American

captain, James Willing. Willing and his party were on their way to New Orleans,

where he would obtain some assistance and supplies for the American

revolutionaries from the Spanish governor, Bernardo de Galvez. Along the way,

Willing was recruiting men who sympathized with the American cause, and burning

the homes and crops of those who did not. Selkrig, a loyal Britisher, was taken

prisoner, thrown aboard the Rattletrap, and carried away by the raiders.

Fortunately for Selkrig,

British friends rescued him before the boat reached New Orleans. He returned to

his little plantation at The Three Islands, only to find that Indians had

plundered his cabin and fields in his enforced absence. Fearing for his own

life, he abandoned his farm and moved down the river into a more settled area.

There were no further

efforts to establish plantations in the vicinity of what is now called Davis

Island until it became apparent that the United States was about to settle its

boundary dispute with Spain, and that the Old Natchez District would become

American property. American settlers rushed in to establish claims and a

settlement called Palmyra sprang up on the east bank of the river in the bend.

When the United States

opened a land office to settle land titles and dispose of government land,

William Selkrig filed his claim to the land where he had built his little cabin

in 1777. His title under the British land grant was held to be invalid, and the

preemption claims of squatters in the area were recognized.

In 1808, Edward Turner, a

Natchez lawyer, began to purchase the small tracts of land claimed by the

Palmyra squatters, and by 1810 he had acquired the whole settlement on the

north side of the peninsula of land in the big bend. Turner was joined in 1818

by another purchaser, Joseph E. Davis. who acquired most of the land on the

west side of the peninsula. An adjoining property became the home of Joe Davis'

younger brother. Jefferson Davis.

The two Davis plantations.

Hurricane and Brierfield became well-known and the bend of the river was

renamed Davis Bend. When the Union campaign against Vicksburg was under way in

1863, both the Davis plantations were confiscated. Jefferson Davis, who had

been a hero of the War with Mexico, a United States Senator, and U. S.

Secretary of War, was now the President of the Confederate States of America,

and Union authorities thought it was particularly fitting that the plantation

that had belonged to the highest ranking rebel of all should be appropriated

for use by the Freedmens' Bureau. A model colony was to be set up to

demonstrate that the ex-slaves from the southern plantations would quickly

become self-supporting, given an opportunity. Cotton speculators thwarted the

good intentions of both the black farmers and their government supervisors, and

the colony was not a success.

After the war ended, Joseph

Davis regained possession of the land in Davis Bend by signing an oath of

loyalty to the Federal Government. He swore to Union military officers who

administered the oath that he had taken no part in the rebellion and had given no

aid or encouragement to the Confederacy of which his brother had been the first

and only President. Jefferson Davis, on the other hand, steadfastly refused to

take the oath, saying that he would never beg for favors from the Federal

Government. He had sincerely believed in the right of a state to secede, and he

saw no need to "repent" of actions undertaken in good faith.

Two years after the war had

ended, a natural cutoff occurred, and the peninsula in Davis Bend became an

island. The Davis Cutoff removed about 25 miles of navigation channel from the

river, but the reach was an unstable one that soon began to change again. In

1904, the Mississippi broke through a narrow neck of land at Killikrankia

plantation and reclaimed its old bed in Davis Bend. When Diamond Cutoff was

opened in 1933 the old bendway around Davis Island filled at both ends and the

river permanently abandoned it.

The oxbow lake that was once Davis Bend is called

Palmyra Lake today, and has become a popular fishing and hunting area for both

Louisiana and Mississippi residents. The homes of the Davis family no longer

stand, and the island is now a vast plantation where beans, cotton, and cattle

are raised. It is separated from Mississippi by the river, and from Louisiana

by Palmyra Lake and swampy areas, and few people ever see it.

The oxbow lake that was once Davis Bend is called

Palmyra Lake today, and has become a popular fishing and hunting area for both

Louisiana and Mississippi residents. The homes of the Davis family no longer

stand, and the island is now a vast plantation where beans, cotton, and cattle

are raised. It is separated from Mississippi by the river, and from Louisiana

by Palmyra Lake and swampy areas, and few people ever see it.