Mound Colony

(Illinois

Central Magazine, August 1931 & Madison

Journal December 22, 1933)

From Cecil Smith scrapbook scanned by Janet Byram Newsom and John Earl Martin

When Mound, La.,

shipped to market eleven carloads of No. 1 Irish potatoes in June this year,

the incident no doubt appeared commonplace enough to the casual observer. To

the informed, however, these potatoes were possessed of deep and romantic

significance. They were freighted with human hopes, with difficulties overcome

and with the evidence of a new order of things. They were the first visible

fruit of a project that is attracting interesting attention not only throughout

the lower Mississippi Valley but also in localities as far away as Michigan,

Minnesota and the Dakotas. They were the first surplus products of the Mound

colonization enterprise, which is fostered by George S. Yerger, land-owner in

Madison Parish, Louisiana, with the co-operation of the Agricultural and Colonization

Departments of the Illinois Central System. Those potatoes signified the

success of crop diversification in a hitherto untried locality.

The potatoes that were shipped from

Mound were raised on farms purchased from the Maxwell-Yerger estate within the

last three years by colonists who migrated to Louisiana from the North,

principally from Minnesota. They came at the solicitation of representatives of

the Illinois Central System Colonization Department and the Yerger

organization, in cooperation with F. E. Spring, of the Louisiana Delta Farms

Company, Plymouth Building, Minneapolis, Minnesota. The transplanting of these

farmers from the North to Madison Parish, Louisiana, is expected to hasten

changes in agricultural practices that will make cotton an auxiliary to a

widely diversified farm industry throughout the entire region, the climate and

fertility of which make it a land of limitless possibilities.

Five Flags Waved Over

Region

The productivity of

the Mound region was appreciated by the aborigines long before the written

history of this country began. The great mounds, from which the town takes its

name, prove that the Indians dwelt there centuries before the coming of the

white man. From the time that DeSoto, the Spanish explorer, first set eyes on

the territory, five flags have flown in turn in the Delta-land breezes to

prove its desirability — those of Spain, France, the United States, the

Confederacy and again the United States.

More than a century

ago, the amazing fertility of the land now comprised in the Maxwell-Yerger

estate, at present about 24,000 acres, was famed throughout the South. It is

situated in the alluvial deposits that lie across one of the great bends of the

Mississippi River opposite Vicksburg, Miss. The tract demonstrates that the

great river is not only the "Father of Waters" but is also the

"Mother of Lands." For uncounted centuries the silt-laden overflows

of the river built up this land until, with the recent construction of the

United States Government's giant flood-control levee at the end of the estate,

which closes it against the river perhaps forever, its life-impregnated soil

had acquired an estimated average depth of 100 feet or more.

While a well was

being dug on the estate not long ago, a cypress tree trunk in a good state of

preservation was found at a depth of eighty feet. No one knows the thickness

of the soil in which the old cypress imbedded its roots, but it indicates that

the Delta's fertility goes far deeper than ever can be touched by plow or the

probing roots of any living plant.

$100 An Acre 75 Years

Ago

Madison Parish records show that

practically the same 24,000 acres now in the Maxwell-Yerger estates comprised

the property of the John Hoggatt family before the Civil War. With the death of

John Hoggatt, the estate was divided among the heirs and from then on it

dissolved into a large number of small holdings. The old records show that in

1856, when it was the Hoggatt estate, the land sold for $100 gold per acre, a

tremendously high price for that day in the South. In pre-war days the entire

estate was devoted to the culture of cotton with slave labor, and cotton

continued practically the sole product of the land after the dismemberment of

the estate.

The story of how the

broken-up estate was reassembled begins with the siege of Vicksburg in the

Civil War. One of the soldiers in General Sherman's and later General Grant's

forces during the Vicksburg campaign was Friend L. Maxwell of Sullivan, Ind.

After his return to civil life at the close of the war Mr. Maxwell went to

Louisiana to cast his lot with the life of the community. He undertook a

general mercantile business at Mound. Two times he "went broke," but

he began again and finally achieved success. With the profits of his business

he invested in land until he had accumulated about 12,000 acres.

Another Returns From

the War

Again war was the

forerunner of an event of importance to the estate when Captain George S. Yerger,

returning from the army service in the Spanish-American conflict to his home in

Jackson, Miss., decided to seek his fortune at Mound. There his acquaintance

with Colonel Maxwell eventually ripened into a business partnership. With his

profits, Mr. Yerger also accumulated land until at the time of Colonel

Maxwell's death in 1914 the two men's holdings were about equal, 12,000 acres

each.

Shortly after Captain

Yerger's arrival at Mound, Edna Maxwell, the colonel's only daughter, who had

been away to college, returned home. Immediately the young Spanish War veteran

found favor in her eyes. The romance culminated in their marriage in 1901, so

that when Colonel Maxwell died in 1914 the old estate found itself

automatically reassembled under a single management.

Shortly after Captain Yerger's arrival

at Mound, Edna Maxwell, the Colonel's only daughter, who had been away to

college, returned home. Immediately the young Spanish War veteran found favor

in her eyes. The romance culminated in their marriage in 1901, so that when

Colonel Maxwell died in 1914 the old estate found itself automatically

reassembled under a single management.

As in the days before the Civil War, cotton furnished the principal theme of

the estate's existence. Little attempt was made to cultivate other crops. For

weal or woe, the land and its people abided with cotton. Cotton was the extent

and limit of their existence. If cotton prices were high, as on rare occasions

they were, notably during the World War (WW1),

owners, tenants, employees and dependents prospered. If prices were low, as

they were generally and especially after the close of the World War, the

community suffered. The boll weevil, which came as an intermittent plague, was

but one of the many evils that grew up during King Cotton's terms of misrule.

These evils at length reached a point

where Mr. Yerger decided that the time was ripe for a change. For years he had

been observing the success of the development work of the Illinois Central

System's Agricultural Department in other parts of the lower Mississippi Valley,

and he conceived the idea that equally good or even superior results could be

obtained on the Louisiana side. He believed that, entirely aside from the

merits of long-staple cotton as an agricultural product, other things could be

raised on his land with greater and more certain profit.

Time Ripe for a

Change

In the generation of his plan, many

conferences took place on broad veranda of the Yerger mansion at Mound. Those

who conferred with Mr. Yerger at first were his six stalwart sons, grown to

manhood and sharing in the management of the estate and many Yerger

enterprises, and calm-eyed, prudent and courageous Mrs. Yerger, who knew the

business and prospects of the Maxwell-Yerger organization as well as any of her

own men folks. Then the development men of the Illinois Central System were invited

to participate. H. J. Swietert, general agricultural agent, B. T. Abbott,

agricultural agent at Memphis, took part in the veranda conferences.

It was apparent at

once that the effort to escape from cotton was not to be without its

difficulties. It was the one crop that could be handled by the central management

of a great estate without explanation and instruction on infinite details to

the tenants and employees. It had been the sole care of these people and their

forefathers for so long that its production was almost automatic. Many of the

tenants knew nothing of other crops, and they looked with apprehension upon

any proposed change.

It was agreed at the veranda

conferences that despite the difficulties a change had to be made. The

alternative was bankruptcy or worse. It was proposed that an effort be made to

bring in farmers from the North who were familiar with the cultivation of other

products, with the handling of the necessary machinery and with methods in

dairying, poultry raising and other diversified activities developed in

Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa, Minnesota and other states of the upper valley.

In view of experience

at other places, it was concluded that in order to interest these farmers it

would be necessary to sell them the land. Through a co-operative association of

these farmers, it was argued, the former unified management of the estate

could be retained in large part without loss of the advantages of concerted action

dependent upon centralized authority. Through co-operative association the

farmers could agree to plant potatoes or vegetables or other products at the

times and in the quantities that would make possible shipment in carload lots

and justify the government inspection and standardization, thus guarantying

top prices.

An Experimental Farm

After long and careful consideration of these ideas, it was decided to put

the plan into execution. Two or three false starts were made, with resulting

disappointments and trouble, but in 1928 the organization of the Delta Farms

Company was perfected, and the colonists began to arrive and establish

themselves on the land. The Agricultural Departments of the Illinois Central

System planted about two acres in experimental crops at Mound, the center of

the new operations; a "museum" of the products of the region was

opened in the general store. Practical demonstrations of the quickest-yielding

and most profitable crops were made for the benefit of the incoming farmers.

This year the experimental farm (which

Colonization Agent B. T. Abbott explains to the new colonist; not only keeps

one year ahead of them in the planning of new crops but also tries various ways

of planting and cultivating each crop in order to determine the best method)

had two varieties of lespedeza, two varieties of peanuts, garbanzo (chick

peas), upland rice, grohoma, popcorn, ten varieties of soy beans and ten varieties

of peas, corn, clovers and potatoes. Several crops a year on the same acreage

being the rule in the Mound region because of the brevity of the winter (which

is no winter at all in the opinion of the colonists from Minnesota), the

experimental farm also works out the best rotation of crops and the most

appropriate time of the year for their production.

One Hundred Families

Located

Last year (1930) thirty colonist families located

on farms sold out of the Yerger estate. This year the number increased to 100,

and it was expected that before the close of the year all of the land available

in the Yerger holdings would have acquired new owners, it being Mr. Yerger's

plan to retain 4,500 acres of the original estate in the Yerger family's

possession.

These colonists are

experienced farmers with some financial resources. Some had bought equities in

land in Minnesota and other northern states and then through deflation in land

values found their equities practically wiped out. Others are farmers who saw a

chance to make more money in Louisiana. Still others had been renters in the

North. All were ready for the change.

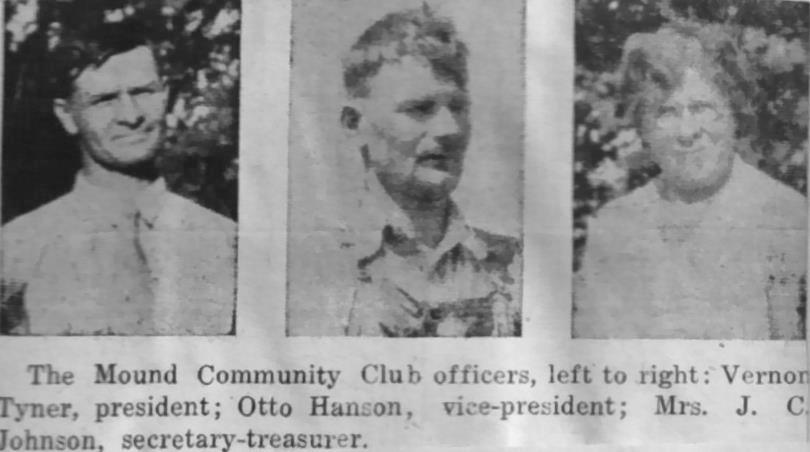

One of the first acts of the colonists,

under the suggestion and guidance of Mr. Yerger and the Illinois Central

Agricultural Department, was the organization of the Mound Community Club, of

which every man, woman and child of the newcomers is an active member. Meetings

are held once a month, rain or shine, whether it be planting time or harvest

time, and up to now no member has ever missed a meeting except because of

illness. The serious business of the club is disposed of at the meetings

first. This usually includes talks on farm topics, exchange of experiences and

plans for community activities, such as the planting of some special crop for a

definite purpose. This crop is decided upon as a result of observations on the

experimental farm and in view of market opportunities. With this business out

of the way, the social part of the program begins. The women lay out the

refreshments. Then there is dancing to music furnished by local talent, cards,

other games and just visiting.

Club Is a

"Life-Saver"

The community club,

as was foreseen in the veranda conferences, proved a life-saver for the colonists.

It not only enabled them to work out their associated farm activities but it

eased man, woman and child over the first period of home-sickness which it was

human nature to feel as the result of having left old homes for new.

Vernon Tyler,

formerly of Cannon Falls, Minn., is president of the club. He brought one of

the best herds of dairy cattle ever raised in Minnesota with him to Louisiana,

and he found opportunity waiting him in the form of a profitable business in

which he furnishes milk and other dairy products to the citizens of Tallulah, a

hustling city not far from the Mound development.

Otto Hanson, also

from Cannon Falls, is vice-president of the Mound club. He and his

brother-in-law, Albert Peterson, and their families are farming with Minnesota

methods in a land of fertility and benignity of climate that surpasses

anything they had ever imagined. The two families live together in a house

that they have just built, and they will have a house for each family before

the end of another year if their affairs continue on the present profitable

basis.

Mrs. J. C. Johnson is

secretary and treasurer of the Mound club. She and her husband are also from

Minnesota, and they have the kind of place and are living the kind of life that

they used to dream about without ever really believing it would come true.

A Story of Human

Interest

K. E. Byson, formerly

of St. Cloud, Minn., and one of the most active members of the club, declares

that one of the fondest ambitions is to "write a book about" the

Mound colonization. He said he would describe the human interest features of

the colony; how the first year with its hopes and doubts changed into certainty

of experience in the second year; how northern-bred farmers had to make

adjustment to new environment; how success finally came out of an admission of

past errors, observation of the progress of others and taking full advantage

of the land's amazing opportunities.

Another of the

colonists, who looks upon life with a quizzical philosophy, voiced some of his

impressions of his new surroundings and his southern neighbors as follows:

"Our southern friends say that

they want to get away from cotton. But I don't know. It seems as if cotton is

in their blood. Cotton is one thing they feel sure about. The cotton planter is not the only one who feels that way.

The merchant, the banker, everyone feels that way.

There

is a banker not far from here, for example, who is strong for crop

diversification. He advocates diversification at the Rotary Club meetings and everywhere. Not long ago, however, one

of the colonists ran short of cash and, knowing the banker's attitude, went

to him for a loan. The banker greeted him cordially,

and the farmer revealed his mission. The banker then asked the farmer how many

acres he had planted.

Theory and Practice

"The farmer replied, `Twenty

acres in corn, ten acres in soy beans, two acres in potatoes,” and then stopped

because of the disappointed expression on the banker's

face. The banker said, "that is very interesting, but when I asked you how

many acres you had planted I meant how many acres of cotton.' "

J. J. Goar, formerly

employed in a factory in Minneapolis but experienced in farm work in his

youth, feels definitely established on the road to prosperity in his second year

at Mound. He shook his head at the mention of cotton, but, pointing a bronzed

hand at a nearby field of potatoes, he quoted the famous line, "Thar's

gold in them thar hills."

A. S. Aronson,

formerly of Minneapolis, typified the attitude of the newcomers toward cotton

when he said “It may be all right for those who understand it, although I

notice that they do considerable complaining, but as far as I am concerned I

prefer the crops to which I am accustomed. My experience has taught me how to

raise grain and vegetables and livestock, and there never was a better place on

this earth to do these things than right here. This colony is going to make

money, and plenty of it, but I doubt that much of it will come from

cotton."

Development Attracts

Attention

The colonization

effort of the Yerger organization is being closely watched by the other large land

owners in the vicinity, and for that reason the Illinois Central Agricultural

Department believes that the Mound colony has an especially profitable

opportunity in the new crops that are being introduced and cultivated by the

colonists. Agricultural Department officers' look forward to the day when Mound

seeds will be prized throughout the entire lower Mississippi Valley.

The potatoes marketed

by the colonists this year netted them as high as $70 an acre, and plans discussed

in the community club indicate that next year's potato acreage will be several

times as large as this year's. Mr. Yerger predicted that next year's shipment

of potatoes will probably run between 100 and 200 cars, with other crops also

reaching carload shipment proportions.

The colonists are

astonished at many possibilities of the neighborhood. The oldest commercial

paper shell pecan grove in the country borders on their property. Pecan trees

grow wild in the surrounding forests. Small-fruits grow in a manner never

known in the North. The orchards are loaded with peaches, pears, persimmons,

grapes, apples and figs. They plant and harvest their household vegetable

gardens several times a year. The calendar has changed its meaning. The old

familiar months seem to have moved. They plant cultivate and harvest at times

that recall nothing in their experience But they soon grow to like it.

Colonists Soon Feel

at Home

The northerners are

eager to establish their own farm practices in the region. They smile with contentment

at the sound of the purring tractor pulling their plows and cultivators. The

hum of the threshing machine, pouring forth the familiar grain, is music in

their ears. In the evening, when the day's work is done, the colonist watches

the Louisiana moon climb out of the tree-fringe of the bayou. He hears the soft

lowing of his dairy herd, and there creeps over him a feeling of content and

well-being, a feeling that he is at home.