Mosquito Experiments at

Mound

From the August 14, 1975 Centennial Edition Madison Journal

Since about 1890, the U.S. Bureau of Entomology has

conducted investigations into the mosquito. Long before any mosquitoes had been

incriminated as a disease-carrier, the bureau had justified its work because of

the discomfort to humans and animals caused by the bites of these annoying

insects.

Working in the respective fields of malaria and yellow

fever, Ronsen Ross, an Englishman, and Walter Reed of

the United States demonstrated around the turn of the century that certain

mosquitoes are the intermediate hosts of the organisms causing the two

diseases.

With this revelation, the work of the Bureau of Entomology

on mosquitoes took on a new impetus. The Bureau undertook studies to determine

the species of mosquitoes transmitting disease in this country. The new

investigations were pushed by a leading insurance company, as well as by

Governors and Congressmen in the Southern states, where malaria was the most

widespread.

Malaria, now almost completely wiped out in this country,

is a long-lasting disease with intermittent symptoms. It is caused by a

parasite which reproduces asexually. When the parasite divides, usually every

three days, the host victim experiences chills. Malaria can remain dormant for

years until a bad illness or accident produces symptoms.

The economic effects of malaria were felt mainly in

absenteeism due to sickness. The sawmill at Mound would almost have to hire two

men to get the work of one. Madison Parish had the highest per capita rate of

purchases of quinine and chill tonic (the commonly sold malaria cures) of any

parish or county in the country.

Such evidence of Madison's high rate of malaria convinced

the Bureau of Entomology to establish an experimental laboratory there. The

"mosquito lab" was set up at Mound in 1913 to provide a center where

suitable facilities would be available to carry on and expand earlier studies

on disease-carrying mosquitoes.

Mound was selected as the site for the laboratory partly

because the local authorities, Col. F. L. Maxwell and George S. Yerger offered

full cooperation in carrying on the work, as did Alex Clark, manager of Hecla

Plantation, and Dr. William P. Yerger, the resident physician.

The work program as outlined initially included

investigations to determine the actual losses to rural industries caused by

malaria carrying mosquitoes; the local and regional distribution of such

species of mosquitoes; their breeding places and habits under the peculiar

conditions making for parasite development and transmission of the parasites to

humans; and the development of appropriate prevention and control methods.

During the ensuing years that the laboratory was

continued at Mound, the staff engaged in a great variety of activities having

to do with malaria and mosquitoes. The results of these were reported on before

scientific groups at meetings and conferences, and duly published in appropriate

journals.

Many investigations were initiated to determine the

relative values of various anti-mosquito and anti-malaria measures such as

screening, the use of medications, insecticides and repellents, clearing and

drainage, impoundment of waters. etc.

The Mound laboratory did the first experimental work in using

fluctuating water levels to control mosquito development. Walnut Bayou was the

scene of these early experiments. Also, using airplanes supplied by the boll

weevil station, the mosquito lab did the first airplane spraying of mosquito

larvae.

The information assembled as a result of these studies

contributed greatly toward the later preparation of a "mosquito

bulletin" under the authorship of W.V. King. George

Bradley and Travis McNeel. The bulletin,

entitled "The Mosquitoes of the Southeastern United States," came

into wide use by workers engaged in mosquito control both in this country and

abroad. A revised and expanded version of this bulletin is now available as

Agriculture Handbook number 173 from the U. S. Dept. of Agriculture.

Over the years that

the laboratory was continued at Mound it was host from time to time, to

numerous specialists, both from this country and abroad, concerned with

mosquito and malaria control problems. They came to observe the activities in

progress and to discuss the problems of a like nature with which they were

faced.

At one time the International Health Division of the

Rockefeller Foundation stationed a number of its staff personnel at Mound,

where they not only studied the activities underway, but carried out a number

of special studies related specifically to their malaria control work in

foreign fields.

The regularly employed staff at the laboratory never was

large, usually numbering not more than three or four professional individuals.

On occasion, principally during the summer months, temporary assistance was

rendered by college students on vacation.

World War I interrupted the work of the laboratory. Three

staff members—A. H. Green, G. H. Bradley and T. F. O'Neil—left during August

1917 and Dr. Van Dine, first director of the station

left shortly thereafter, all to serve as U. S. Army officers for the duration.

In their absence M. T. Young, then assigned to the boll weevil laboratory in

Tallulah, was in charge.

Captains Van Dine and Bradley returned to Mound in late

1919 to continue their activities and were joined about 1924 by Travis McNeel and H. E. Wallace. Dr. W. V. King who had been temporarily

assigned to New Orleans came to Mound about 1920 and was placed in charge of

the laboratory when Van Dine left to accept a position in Pennsylvania.

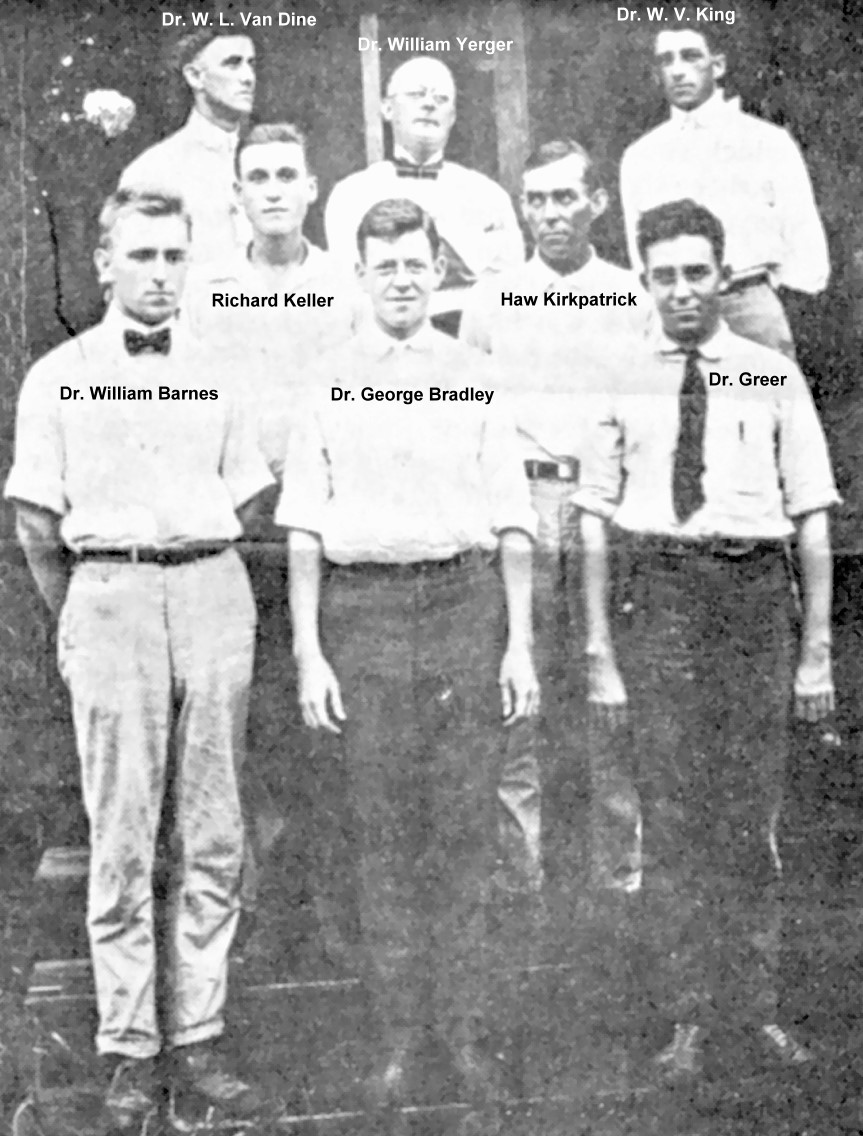

Mound Mosquito Lab in 1917

King, Bradley and McNeel

remained as the laboratory staff until its closing. They went to World War II

in 1941 and all reached the rank of Colonel.

Col. McNeel of course still lives in Tallulah, and is president

of the library board. Another Tallulahan, John

Thompson, was custodian and janitor while the lab was at Mound and was

transferred to Orlando, Fla. when the laboratory was relocated. He since has returned to Tallulah and lives on West Levee Street.

Upon removal of the laboratory to Florida in 1931

emphasis was changed from malaria related activities to those concerned with

the biology and control of so-called pestiferous mosquitoes and other insects

affecting the comfort and health of man. These are still continuing.

About 10 years after the Mound lab was transferred to

Florida, workers in other laboratories developed DDT as an insecticide. This

poison enabled scientists to wipe out malaria in this country.

It had been discovered earlier that the malaria-carrying

mosquitoes would remain outside in the grass, then move into houses and rest on

the walls until night. Then they would feed on sleeping humans and move back to

the wall, where they would stay, heavy with blood, until almost light, when

they would return to the grass.

Since the mosquitoes were on the walls twice every night,

they could be controlled by applications of DDT to the walls of every house.

The Communicable Disease Center, following World War II, provided funds to

spray rural houses of the malarial belt twice yearly with DDT.

The malaria carrying mosquitoes were killed off for a

period, during which time all cases of malaria originating in this country

disappeared.