SINGER

John Earl Martin

NOTE: This is an

interesting history of the Singer Sewing Machine property in Madison Parish and

its relation to the Ivory-billed Woodpecker and the Chicago Mill and Lumber

Company. RPS March 2013.

This is a compilation

of the work of several authors to trace the evolution of a primitive wilderness

to the Singer Game Preserve to the Chicago Mill Game Management area, to a

twenty year span under private hunting clubs, to in some parts soybean and

cotton fields, and in other cases, to over 80,000 acres comprising the Tensas

River National Wildlife Refuge.

This happy ending was

due in a large part to the study of the now-extinct Ivory-billed Woodpecker in

the 1930's and the subsequent dedication of many far-sighted individuals. It is

to these individuals that this paper is dedicated.

John E. Martin 2012

I

FOUNDATION

The War Between the

States left the South a graveyard of ashes and destruction. The people were crippled

and penniless, with their foodstuffs and livestock either stolen by one army or

the other, or destroyed by invading troops. Virtually all their personal

property suffered a similar fate. Likewise, the infrastructure of the whole

country was in shambles, to add to their misery.

However, the southern

forests stood towering over this scene as it had through the ages. Even before

the destruction of the War, few southerners had the wherewithal to harvest this bounty, nor roads or access to streams for its

transportation. Therefore, timber harvest was limited primarily to plantation

owners or a few locals utilizing "groundhog sawmills" to produce

lumber for their homes, stores, and barns.

After the war,

Reconstruction governments took over the South, enabled by Northern troops.

Congress passed laws to prohibit landowners from selling their lands at a

profitable price. One such law prohibited Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia and

Florida from selling any of their public or unclaimed land, which amounted to about

one third of the land acreage in these four states.[1]

The great eastern

forests had long been decimated by the western migration of colonists toward

the Mississippi River. When the Great Chicago Fire occurred in 1871, it caused

such a great harvest of pine timber around the Great Lakes region that by 1880,

it was estimated that only a ten year supply remained. The nation was headed

for a timber famine. But just as the North was running out of timber, a brand

new source opened up. With the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and the departure

of Union troops, southern politicians regained control of their state

governments. Cash-starved Southerners with land and timber met with anxious

Northerners with plenty of money who needed land and timber. The timber boom

was on.[2]

In the South,

investors found land to be plentiful and dirt cheap, and labor plentiful. Poor

whites and freed blacks were willing to work the fields and forests for fifty

cents per day. Vast forests changed hands for virtually nothing. Prices of one

dollar per acre were not uncommon, and one British company got over a million

acres in Louisiana for twelve and one-half cents per acre.[3]

II

COMING

OF SINGER

In 1913, an event

occurred that would have a profound effect on North Louisiana. Douglas

Alexander, president of Singer Sewing Machine Company, bought nearly 83,000

acres of timberland in the area to ensure an ample supply of gum timber with

which to build cabinets for his sewing machines. By then, the land prices had

appreciated to nineteen dollars per acre. He immediately designated the area as

a "Refuge", meaning that no trees were to be cut without his

permission, and as further protection for his timber, no hunting was to be allowed.

Thus was born "The Refuge", the "Singer Tract", or to

locals, simply "Singer".[4]

In 1920, after realizing the problem with locals using the property as a source

of food and fuel as they had for decades, Singer offered the property to the

Louisiana Fish and Game people for management. The State was to hire two

wardens and Singer was to furnish two to enforce trespass and game laws. J. J.

Kuhn, Tom Jefferson, and Ed Cockran were among the

early wardens.[5]

They were joined in 1939 by Jim Parker, Gus Willett, Sam Denton, and Jesse

Laird. Jesse Laird already knew Singer thoroughly, having run herds of cattle

of his own as well as cattle for local owners for several years.[6]

The lands involved in

the sale to Singer shows the intense shuffling of landowners in the maelstrom

of the Reconstruction Era. Major among these landholders were as follows:

The Ashly Company

George C. Waddill

Madison

Parish Levee Board

Friend L.

Maxwell

Britton and

Koontz Bank[7]

Many of these

holdings were abandoned cotton plantations. This is evidenced when walking

through the timber and observing the abundance of levees and drainage ditches

with oak trees growing from them that appear to be 75 to 100 years old.

Between 1913 and

1918, Singer was also able to annex some additional 45,000 acres of the

Fisher-Ayres Tract, bringing Singer's total holdings in Northeast Louisiana to

around 130,000 acres.[8]

III

SAWMILLS

The twentieth century

brought a number of sizable sawmills into Madison Parish. Notable among these

were the Englewood Lumber Company founded in 1904 at the present-day site of

the Richard Harris home on Rosedale. Englewood had over 100 people working and

had fifteen miles of track running into the woods. When all timber near the

track was cut, the company would take up the

track and move it to another cutting site. There was a sawmill at Mound, La.

and there was the Krus Brothers Mill at Tallulah that

was bought by the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company of Greenville, Mississippi in

1928. At Tendal, La The Tendal Lumber Company was established by Lee Kathan and Dave Johnson in 1918. Sondheimer, La. boasted

the Sondheimer Lumber Company mill owned by the Cohn family of Chicago.[9]

IV

IVORYBILL!

Dr. Arthur Allen was

a highly respected ornithologist and professor at Cornell University and a

leading expert on bird behavior. In 1924 Dr. Allen and his wife Elsa went to

Florida to test some new ideas in sound equipment and cameras. While there he

was guided by a young man named Morgan Tindall, who

offered to show him an Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Of course, Allen jumped at the

chance, for Ivorybills' existence had not been reported for years and were

thought to be extinct. They did see a pair and went back to Cornell with

photographs to prove it. So was developed the idea of studying photographs and

behavior instead of studying the dead carcasses of rare birds.[10]

Dr. Allen was immersed in his teaching and doing research on recording bird

sounds, but he never forgot the Ivorybills that he and Elsa had seen in

Florida.

In 1932, a Madison

Parish lawyer and outdoorsman named Mason Spencer took a freshly-killed

Ivorybill to Conservation officials in Baton Rouge. Weeks earlier, these

officials had issued Spencer a permit to "collect" one in response to

his boast of knowing where there was an 'abundance' of them.[11]

Ornithologists rushed

to Baton Rouge and soon verified Spencer's claim. To Arthur Allen, this

appeared as the premier opportunity to perfect a new type of bird study where

the guns were left at home and birds were "shot" with camera,

microphones and binoculars.

Then, in 1934, Dr.

George Lowery of LSU published his famous Birds

of Louisiana, in which the Ivorybill received needed publicity. Thus, the

stage is set for the beginning of a great adventure.[12]

V

EXPEDITION TO SINGER

In 1935 a team left

Cornell University, making a brief foray into Florida, but finding nothing

interesting, headed immediately to Louisiana. The team consisted of Dr. Arthur

Allen, who would film and photograph, Peter Paul Kellog

to run the sound recording equipment, the artist George Sutton for scouting and

for identification of birds, and a young graduate student named James Tanner

"to act in any necessary capacity." The sound equipment had been

bought and assembled by a New York stock broker named Albert Brand. Brand was

supposed to accompany them to perfect the sound equipment in the field, but was

forced at the last minute to cancel out because of sickness.[13]

The 1935 trip was a

great success. The group was guided by J. J. Kuhn, a local man and Singer

warden. They were able to find Ivorybills and to get a multitude of photographs

and sound recordings of the rare bird. (Many pictures taken during Tanner’s studies may be

seen by clicking here.)

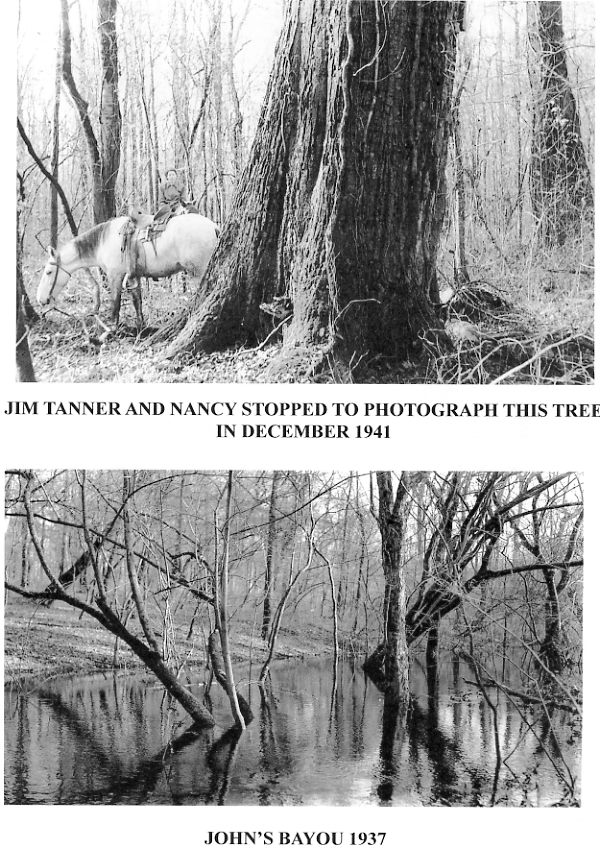

Jim Tanner returned

to Singer in 1937 to study the Ivorybill. This study lasted almost three years.

That same year Singer sold a six thousand acre tract to Tendal Lumber Company

in the area around Horseshoe Lake and Lake Despair. Two years later in 1939,

Singer sold the timber rights on the remaining acreage to Chicago Mill and

Lumber Company.[14]

Tanner had another

serious blow during this time (1939) when he learned that his friend and

companion J. J. Kuhn had defied Governor Richard Leche's

instruction to "get lost" from a certain area of Singer because he

was bringing in a large party to hunt. Leche was so irate when Mason Spencer

delivered Kuhn's reply that he retaliated by cutting Kuhn's salary so severely

that he was forced to resign. Also, Kuhn had undergone the loss of a son

through an accidental

shooting.[15]

By 1940, through the

efforts of John Baker of the Audubon Society and others, the public was

becoming aware of the rapid destruction of the southern hardwood forests.

The publicity

surrounding the Ivorybill and the resulting studies involved played a great

part in this awareness. Even today, some seventy-five years later, the names

"Singer", "Ivorybill", and "Conservation" are

almost synonymous.

VI

WAR TIME

In 1940, John Baker and

the Audubon Society persuaded La. Senator Allen J. Ellender

to introduce a bill to establish the "Tensas Swamp National Park"

which would prevent the cutting and preserve sixty thousand acres of Singer

that remained intact. It was a good bill, but it was not funded. The money

would have to be raised.[16]

Baker then sought and

got an endorsement from President Franklin D. Roosevelt for the bill. He was

also able to get pledges of support from the heads of the U. S. Forestry Services, the U. S.

Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Park Service. In 1942, even

the head of the War Production Board said that he did not consider the complete cutting of the Singer Tract to be

essential to the War effort. Louisiana Governor Sam Jones pledged $200,000 from

the State of Louisiana for the purchase and the governors of the neighboring

states of Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi sent a joint letter to Chicago

Mill urging them to release their lease on the timber. In 1942 Senator Ellender again introduced the bill for the Tensas Swamp

National Park that provided for private funding, but again the bill failed to

get out of committee.[17]

When in 1943 (December) Chicago Mill president Jim Griswold and his counsel met

with wildlife officials, Governor Sam Jones, John Baker, and other interested

parties, Chicago Mill stated its position that it was not willing to even

discuss any plans that would interfere with their plans to complete its cutting

of the Singer Tract in accordance with their contract rights.[18]

Earlier in 1943 with

negotiations stalemated, Dick Pough was sent secretly

back to Singer by John Baker to confirm the continued existence of the

Ivorybill. In six weeks of searching, he had found a single bird--a female. He

sent word to fellow staff member and artist Don Eckelberry

that if he ever intended to draw an Ivorybill from life,

he had better hurry and take advantage of this, perhaps his last opportunity.[19]

Don Eckelberry's two week observation and sketching of the bird

is the last universally accepted sighting of the Ivorybill in the United

States.[20]

Tim Gallagher's Grail Bird has a very interesting

section, especially to locals. Tim visited with Jesse Laird, who stepped in to

aid Jim Tanner after J. J. Kuhn's break with Louisiana politics. Laird had

helped Kuhn the year before, and guided Dick Pough

and Don Eckelberry in 1944. He also talked with

Jesse's son Gene and his friends, the Faught

brothers, Billy and Bobby, and relived with them their experiences with the

artist during that cold winter of 1944. Though quite young by today's standard,

these men were still able to paint a vivid picture of Singer as it was around

the "Steel Camp".[21]

Singer had sold 13,491 acres to Chicago Mill in 1942 in the midst of the

negotiations with John Baker, et al. In January of 1944, Singer sold Chicago

Mill the balance of the acreage.[22]

Chicago Mill's circumstance was much improved in 1943 when some 505 German

Prisoners of War were sent to Camp Ruston's satellite camp in Tallulah. These

men were hardened veterans of Irwin Rommel's Afrika Korps. Nearly all of them could be classified as artisans

of some nature. They welcomed the opportunity to work on the farms and forests

of Madison Parish. They were paid fifty cents per day, fed the same rations as

their guards, and transported by truck to their work sites. These men were a

boon to Madison parish in general and to Chicago Mill in particular. Farms and

forests had no labor force, as all men between ages 18-35 were in the military

along with many young women. Chicago Mill was having to recruit women to work

in the sawmill, especially in the box factory, so these prisoners were a great

help. With this impetus, Chicago Mill was able to run its facility 24 hours a

day.[23]

VII

WAR'S OVER

At the end of World War

II, Chicago Mill had the pleasant task of sating the appetite of the peacetime

housing boom. The "Reserve" was still under a lease agreement with

the State and still protected by State wardens. Many of these names are

remembered today: Jesse Laird, Jim Parker, Tolbert Williams, J. D. McGraw, Oran

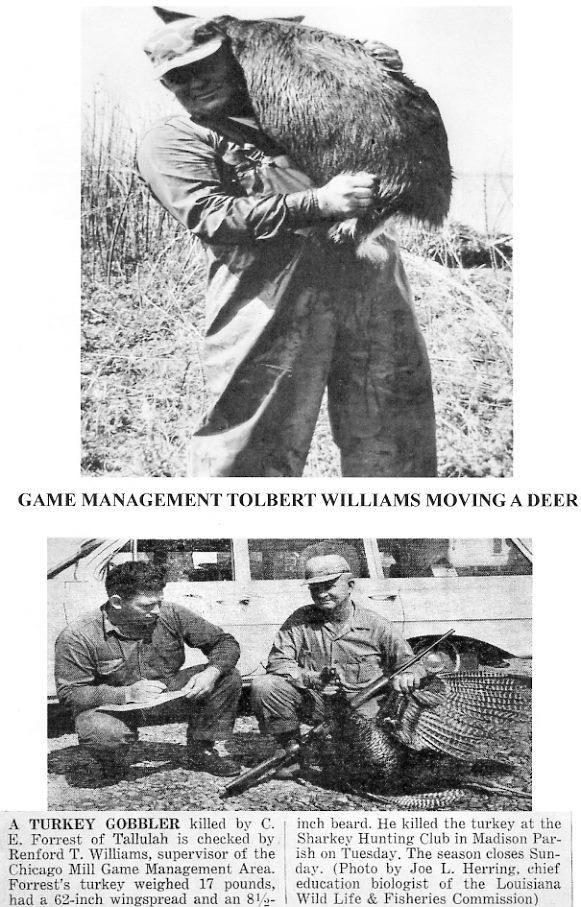

Lewis, Jimmy Willhite to name a few.

As a sort of epilog

to the saga of the Ivorybill, in December of 1948 one of Jim Tanner's former

students, Arthur MacMurray visited the Singer Tract

in the vain hope of finding evidence of an Ivorybill. Tanner had provided him

with contact information and was anxiously awaiting word from him. On January

8, 1949 MacMurray wrote:

"The Singer

Tract has been cleaned of all its commercial timber as far as I could gather.

No Ivorybills have been seen at John's Bayou for at least three years,

according to a resident who has lived adjacent to it for twenty-two years.

John's Bayou has a railway for lumber passing through it and passing all the

way north to some point west of Tallulah, The Ivorybills left Johns Bayou soon

after the large gum tree which had been their nest tree for several years was

lumbered."

MacMurray goes on to say:

"Only one

pair was believed to be in the entire region, having been seen in December of

1948 near North Lake #1 and that they appeared to be wandering over a much

larger area than before"

The last stands of

old sweet gums were being cut at the time. This sighting, a second hand but

highly reliable report took place on E. C. McCallip's

property on the Little Fork Road south

of Waverly on December 17, 1948. Anxiously MacMurray

visited McCallip's on December 23, 1948, but found

only cut-over timber.[24]

VIII

GAME MANAGEMENT AREA

In the late 1950's

Louisiana made the decision to open all of Singer to the public as a game

management area. Parts of Franklin and Tensas Parishes opened in 1958 and

Madison Parish in 1960.[25]

Considerable progress was made in game management and much information was

garnered from the undertaking. Perhaps this could be called Louisiana's real

entrance into modern game management. This phase ended in 1965 with the

acquisition of the property by the Pritzker family of

Chicago.[26]

IX

CLUB RULE

With the change in

ownership, Chicago Mill began leasing its woodlands to private hunting clubs.

These leases were of varying sizes and were leased primarily to area sportsmen

who found a ready supply of members anxious to join, work on, protect, and to

pay for the privilege of hunting thereon. These clubs were immensely popular

with hunters of the entire area. This period could probably be considered the

hey-day for northeast Louisiana hunters.

X

CLEARING PARADISE

In the late sixties,

with soybean prices soaring and most of the good timber gone, Chicago Mill management

could see vast increase in revenue in farming. The cutting tractors began to

roll. As the trees were cut and piled and in some cases still burning,

land-hungry farmers began planting soybeans amid the debris left from the

clearing. As early as 1967, a vast area was opened in Southwest East Carroll

Parish, followed immediately by huge tracts in Tensas and Franklin Parishes.[27]

These tracts, even after these many years, are still referred to as "out

on Chicago Mill" or down on Chicago Mill, etc.

XI

FINALLY CONCERN

Witnessing this

carnage around 1970, people began to be really concerned. These people were not

your usual "tree-huggers". They were not overly concerned with

wildlife or ecology, the past or probably not the future, but this destruction

had them concerned. This feeling is echoed by this letter to the editor of Madison Journal, a weekly newspaper in

Tallulah, LA dated in the summer of 1975:

IMPRESSIONS

Dear Editor:

Have you smelled

the smoke around town lately? The cool nights have caused a temperature

inversion which keeps the smoke low and fairly stable. It's particularly

prominent south and west of town. It emanates of course, from the multitudes of

burning windrows of former woodlands. The smoke, however, seems to contain

subtleties not entirely characteristic of burning logs. After a little

sniffling around, I have been able to separate some of these intangibles. It is

the odor of tens of thousands of songbirds and small animals, thousands of

deer, hundreds of turkeys and the last of the bear. It is millions of these

creatures yet unborn.

It is your great grandfather's first buck and your great grandson's also. It's

Broken Bow, Ten Lick, Madison Recreation and others. It's a family drive

through the woods on an autumn evening. It is the legacy of Teddy Roosevelt and

Ben Lilly. It was virgin forests, Ivory-billed woodpeckers, wolves, cougars and

enchantment.

It is wealth in

saw-logs for those who don't need it and poverty in flooded soybean markets for

those who struggle. It is destroyed roads, ineffective politicians and passive

citizens.

It is a funeral

pyre of our heritage past, present, and future.

Sincerely Billy

Gruff

Long after the

ancient forest that was Singer was gone, the Tract finally became a national

wildlife refuge. Public Law Number 96-285 was approved in June 1980. This bill

directed the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of the Army to

purchase a refuge of about 50,000 acres in Madison, Tensas and Franklin

Parishes. There was still cutting going on, and Chicago Mill was still very

much involved, and controversy continued to reign. This time, however, the

lands were secured and the dozers stopped.

Then in 1985 Public

Law Number 99-191 provided more funds for acquisition of Tensas Refuge lands.

In 1985 as plans were being made for the Visitor Center, James (now Doctor)

Tanner visited Madison Parish and Singer. He and Tuck Stone, refuge manager,

were able to walk in the Tract and reminisce about the forest that had been and

the birds that Tanner had followed day after day during the years 1935-1941.

Finally on June 25, 1998, the Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge was

dedicated. Senator John Breaux presided, Louisiana Governor Buddy Roemer,

Representative Jerry Huckaby, and James Pulliam,

Regional Director of U. S. Fish and Wildlife, all spoke, as well as local

dignitaries. There were two other special guests--two mounted Ivorybills,

specimens from Cornell University, quite possibly collected on Singer.

XII

CHICAGO MILL NOTES

Lets

back up a bit and cover some of the dramatic changes that took place within

Chicago Mill. Chicago Mill and Lumber Co. was founded

in 1828 by Walter Paepcke by the merging of four

lumber companies from Memphis. The company headquartered at Greenville,

Mississippi with main offices in Chicago. After a restructuring in 1933 brought

on by the depression, Chicago Mill began contractual arrangement for its

logging operations. By 1980, Chicago Mill owned over 200,000 acres, mostly in

Louisiana.[28]

The Tallulah Mill was bought in 1928 from the Kruz

Brothers.[29]

In February, 1964, John Maher, a director of the corporation from Houston,

Texas, instigated a dissident's raid on the corporation to gain control. At

that time he claimed to have twenty percent of the 508,000 plus shares of the

stock. A bitter proxy fight ensued that lasted for two months and finally ended

in victory for the management.

In late 1964 Mr.

Maher sold his stock to Mr. Jay Pritzker, a Chicago

attorney and Maher stepped out of the picture. Mr. Pritzker

and his associate Mr. W. H. Gonyea, a West Coast lumberman, tendered an offer to

Chicago Mill's Board of Directors to purchase the assets and assume the

liabilities of the corporation.

The offer was

considered by the Board who subsequently recommended acceptance of the offer,

which was the best they had ever received for the Stock. The offer was accepted

by the stockholders. On June 29, 1965 the corporation ceased to exist and

entity continued as a partnership using the same name.[30]

Examination of parish records show that the Tallulah plant and the Newellton

plant and the property and rights-of-way involved sold to a Mr. Albert Sandel and the land went to Mr. Simon Zunamon,

who was chief accountant for the Pritzker family.[31]

Even to this day people occasionally express surprise that after some eighty

years as a corporation, the entity becomes a partnership. It is usually the

reverse order. Checking dates against events, it is evident how internal

changes affected conditions on the Singer Tract.

XIII

THE 80'S

With this sketchy

background, let's go back to the 1980's. The discord noted earlier led to

several organizations that sprang up to aid Dick Pugh's Nature Conservancy and

John Baker's Audubon Society. Notable among all was the Tensas Conservancy

Coalition, founded in 1981 by Skipper Dickson and aided by Dr. Michael Caire at a meeting of some 75 people representing 30

different conservation organizations including DU, LA, Coon Hunters, La.

Wildlife Federation, La. Wild Turkey Federation, Ouachita Wildlife Unit,

Ouachita Sierra Club, Monroe Jaycees, Ozark Society and others. Their primary

tactic was for the representatives to return home and inform their members of

the urgency of the situation and to launch a campaign to notify the various

officials of their feelings and if possible, to put pressure on ones who were

against the acquisition. Some of this opposition was at home from some farmer

and hunting clubs. But when they came face to face with the alternative, they

became supporters also.[32]

XIV

NOW

The dedication ceremony

for the Refuge was held on April 1986. On this occasion, Amy Ouchley, staff writer for the Madison Journal (and wife of Refuge Manager Kelby

Ouchley) wrote:

"The work

to save over seventy thousand acres of the Tensas swamp conducted over the last

six years was accomplished by a diverse group of government agencies and

individuals who gathered on the stage of the Tallulah Elementary School (here

because of inclement weather) to applaud each other's efforts!"

On hand for the event

were representatives of the Tensas Conservancy Coalition, the U. S. Fish and

Wildlife Service, U. S. Corps of Engineers, La. Department of Wildlife and

Fisheries, Madison Parish Police Jury, U. S. Representatives John Breaux and

Jerry Huckaby, Rep. Francis Thompson and others.

During the ceremony Skipper Dickson praised the acquisition effort as one of

cooperation, and called the purchase "the biggest land deal since the

Louisiana Purchase." Further lauding the cooperation, Sen. John Breaux

said "no other refuge has enjoyed the public support that this one has.”[33]

The following

paragraph is from an unpublished essay by Jim Tanner that was given to author

Tim Gallagher by Mrs. Nancy Tanner when he interviewed her in 2004, after Jim's

death in 1991 of a brain tumor.

"We--the woodpeckers,

Jack Kuhn, and I--lived in the forest, and I came to know it well. It was a

bottom/and forest of oaks, sweet gum, wild pecan, hackberry and several other

kinds of trees covering over a hundred square miles. At the time of my living

there almost all of this was virgin swamp timber, a beautiful forest with many

big trees. A few small cotton plantations had once been cleared and cultivated,

but had long since been abandoned to and reclaimed by the forest. The

primitiveness of the area was its greatest charm. All the animals that had ever

lived there in the memory of man, excepting the Carolina parakeet and the

passenger pigeon, still lived there. The hand of man had been laid so lightly

on the deeper woods and its inhabitants that it took an experienced eye to see

the traces that had been made. The naturalness of the area became more real and

impressive the longer I lived and the more I learned in the forest”

I know that looking

down, the Arthur Allens, and John Bakers, the Dick Poughs, the J. J. Kuhns and Jim

Tanners, the Mason Spencers, the Jesse

Lairds, and Jim

Parkers, Tom Jeffersons and Tolbert

Williams, and a myriad of woodsmen long since gone, would be proud of their

Singer, and would know that finally, we cared.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The

News Star, Monroe, LA 1982

Bales, Stephen Lyn, Ghost Bird, Knoxville: University of

Tennessee Press 2010

Gallagher, Tim. The Grail Bird.

New York, 2005, 93-98

Hoose,

Phillip. The Race To

Save The Lord God Bird. New York: Melanie Kropa

Books, Harra Strauss, and Giroux, n.d.

Jackson, J. A. In Search of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, Smithsonian Books, Harper

Collins, 2006

Moncrief,

Robert L. The Economic Development of the

Tallulah Territory, Thesis, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University, 1937

Ouchley,

Amy. The Madison Journal, April 16,

1986

Shipley, John R. The Story of Chicago Mill and Lumber Company,

Greenville, MS. Unpublished paper

Tanner, James T. The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, Mineola,

NY, Dover Publications, 1942

Terres,

John. Discovery, New York: J. B.

Lippincott, 1961

Williams, Geneva, ed. Minnie

Murphy's Notes on Madison Parish. Madison

Historical Society (1996) p 52